This week we’re back on the topic of IFR flight. If you’ve missed our previous posts touching on IFR, check out these posts:

- Regulations: “Minimum” IFR Training

- IFR: Flight at Mid-Level Altitudes

- CFI Brief: An Introduction to the Instrument Rating

- CFI Brief: IFR ATC Clearances

We’ve also written extensively on the flight instruments themselves too, all of which you can find here. Today’s post comes from The Pilot’s Manual: Instrument Flying (Volume 3).

The first step in becoming an instrument pilot is to become competent at attitude flying on the full panel containing the six basic flight instruments. The term attitude flying means using a combination of engine power and airplane attitude to achieve the required performance in terms of flight path and airspeed.

Attitude flying on instruments is an extension of visual flying, with your attention gradually shifting from external visual cues to the instrument indications in the cockpit, until you are able to fly accurately on instruments alone.

Partial panel attitude instrument flying, also known as limited panel, will be introduced fairly early in your training. For this exercise, the main control instrument, the attitude indicator, is assumed to have malfunctioned and is not available for use. The heading indicator, often powered from the same source as the AI, may also be unavailable.

Partial panel training will probably be practiced concurrently with full panel training, so that the exercise does not assume an importance out of proportion to its difficulty. You will perform the same basic flight maneuvers, but on a reduced number of instruments. The partial panel exercise will increase your instrument flying competence, as well as your confidence.

An excessively high or low nose attitude, or an extreme bank angle, is known as an unusual attitude. Unusual attitudes should never occur inadvertently but can result from distractions or a visual illusion. Practice in recovering from them, however, will increase both your confidence and your overall proficiency. This exercise will be practiced on both a full panel and a partial panel.

After you have achieved a satisfactory standard in attitude flying, on both a full panel and a partial panel, your instrument flying skills will be applied to en route flights using navigation aids (NAVAIDs) and radar.

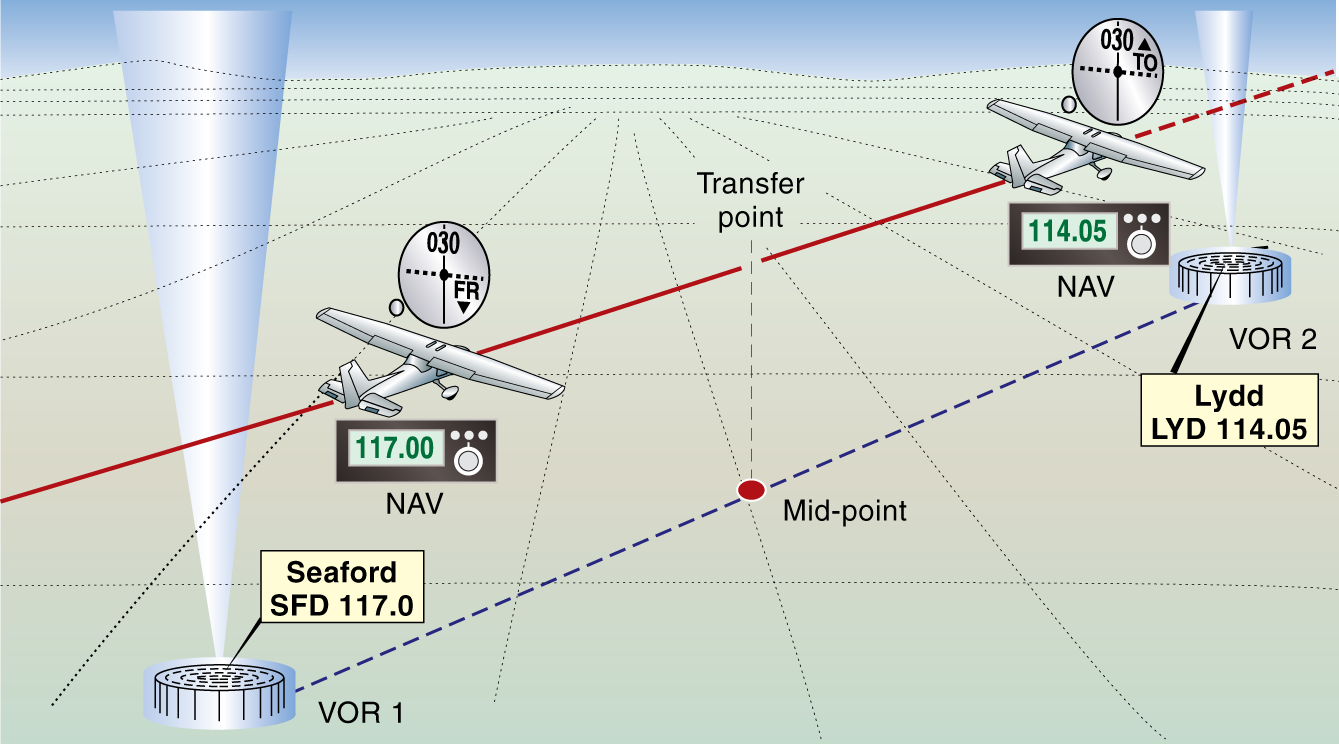

Procedural instrument flying (which means getting from one place to another) is based mainly on knowing where the airplane is in relation to a particular ground transmitter (known as orientation), and then accurately tracking to or from the ground station. Tracking is simply attitude flying, plus a wind correction angle to allow for drift.

Typical NAVAIDs used are the ADF, VOR, DME and ILS, as well as ground-based radar. In many ways, en route navigation is easier using the navigation instruments than it is by visual means. It is also more precise.

Having navigated the airplane on instruments to a destination, you must consider your approach. If instrument conditions exist, an instrument approach must be made. If you encounter visual conditions, you may continue with the instrument approach or, with ATC authorization, shorten the flight path by flying a visual approach or a contact approach. This allows you to proceed visually to a sighted runway.

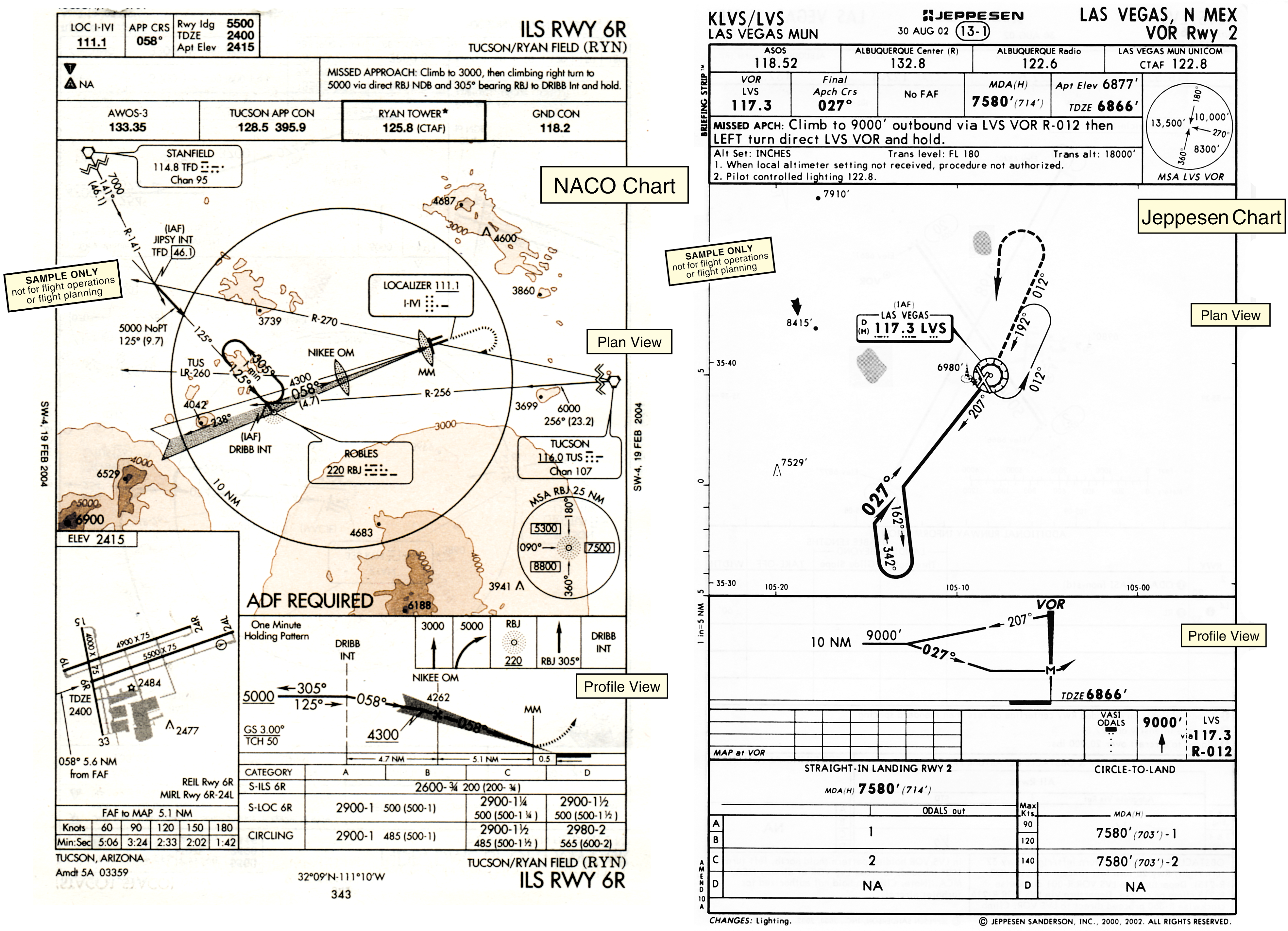

Only published instrument approach procedures may be followed, with charts commonly used in the United States available from the FAA or Jeppesen. An instrument approach usually involves positioning the airplane over (or near) a ground station or a radio fix, and then using precise attitude flying to descend along the published flight path at a suitable airspeed.

If visual conditions are encountered on the instrument approach at or before a predetermined minimum altitude is reached, then the airplane may be maneuvered for a landing. If visual conditions are not met at or before this minimum altitude, perform a missed approach. The options are to climb away and position yourself for another approach, or to divert elsewhere.

It is important psychologically to feel confident about your instrument flying ability in an actual airplane, so in-flight training is important. There will be more noise, more distractions, more duties and differing body sensations in the airplane. G-forces resulting from maneuvering will be experienced, as will turbulence, and these may serve to upset the inner senses. Despite the differences, however, the ground trainer can be used very successfully to prepare you for the real thing. Practice in it often to improve your instrument skills. Time in the real airplane can then be used more efficiently.

Editor’s note: We will continue to expand on these principles in Thursday’s post and in later ground school posts. If you’re starting to think about getting your instrument rating, or are already flying with one, check out ASA’s selection of books on airmanship. For private pilots I would recommend IFR for VFR Pilots by Richard Taylor, Instrument Flying Refresher by Richard Collins and Patrick Bradley, and A Pilot’s Accident Review by John Lowery. Instrument rated pilots should check out Flying IFR and ATC & Weather: Mastering the Systems by Richard Collins, and Severe Weather Flying by Dennis Newton. We’ll see you Thursday.