One of my favorite times to fly is during the night or in the wee hours of the morning while it’s still dark. Ever since my first night cross-country flight, I have enjoyed being in the skies when most people are at home sound asleep. Often, flying during these nighttime hours can be a much more peaceful experience; radio frequencies are quieter, air traffic is less, winds and turbulence have settled down a bit, and it’s just you and the open sky. That’s not to say night flying doesn’t come without it’s inherit risks, sometimes more so then flying during daylight hours. One of the greatest differences or associated risks that results from flying under the moonlight is your vision.

Night vision is the ability of the human eye to detect objects at night. The rods and cones that make up the retina of your eye are the receptors which record the image and transmit it through the optic nerve to your brain for interpretation. The cones are concentrated toward the center of your field of vision and are responsible for all color vision and detecting fine detail. Your rods on the other hand are more suited for detecting movement and providing vision in dim light. Unlike cones though, rods are concentrated further away from your center of vision. One downside to rods is the fact they are very light sensitive; any amount of light can overwhelm them and they will need to go through a reset process to adapt to dark. I’m sure this is something you have noticed before. For example when high beam headlights from a car hit you while driving on a dark road you will essentially feel blinded until your rods are able to adjust back to the dim light. It can take the rods up to 30 minutes to fully adjust.

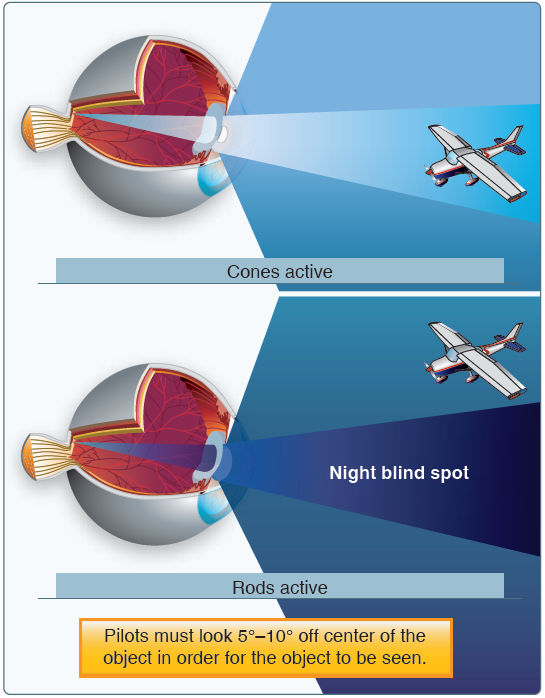

The rods and cones are capable of functioning in both daylight and moonlight, although the process of night vision is placed almost entirely on the rods. It is because of the rods being almost 10,000 times more sensitive to light which makes them the primary receptors for night vision. Since we discussed the cones being concentrated near the fovea (or center of your eye) and rods being concentrated further off center from the fovea it is important to note that the majority of your night vision will be through off-center viewing. Darkness will result in a night blind spot toward the center of your eye where the bulk of those cones are. Rather than trying to look straight on at an object like a plane in the night sky, the pilot is better off looking 5° to 10° off-center exposing the rods to that object as shown in the below image.

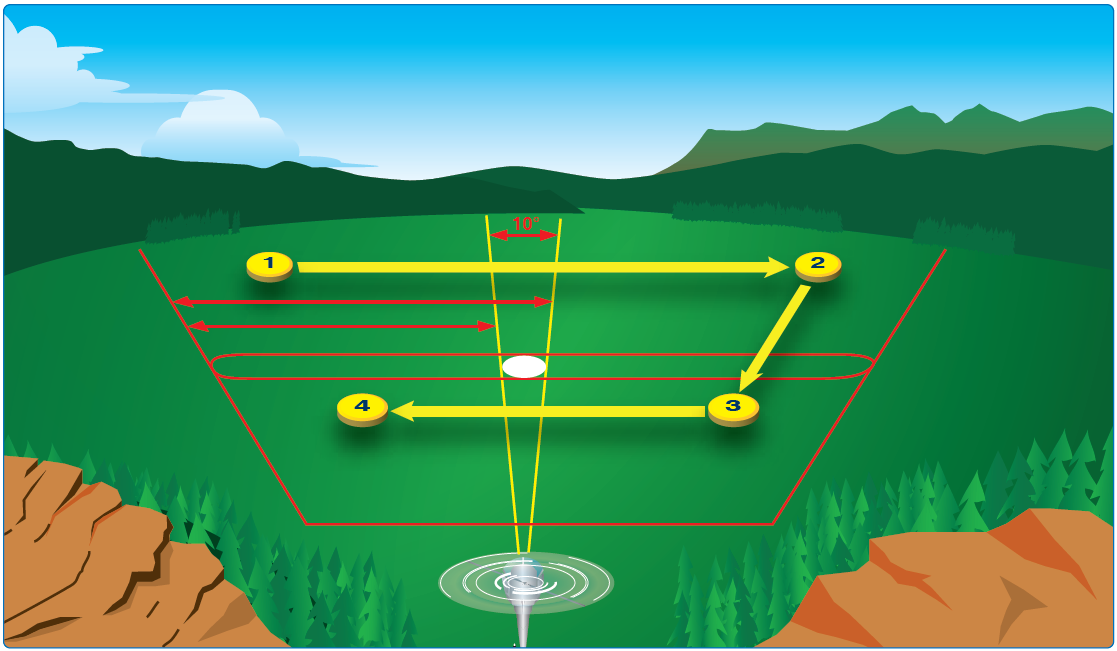

The best technique for night scanning is to scan from left to right (or vice versa) starting at the furthest point the eye can see and move inward toward the airplane. While scanning, you will want to spend about 2 or 3 seconds looking at approximately 30° wide sections of the sky, overlapping each section by 10° as you move to the next. This is depicted in the image below.

One of the most important things you must do during night flying is to protect your night vision. Stay away from bright white lights and keep your eyes adapted to the darkness. Chapter 17 of the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-8083-25) outlines several ways and steps in which you can protect your night vision. If you plan on flying at night it is a must that you fully understand how your eyes function and differ during moonlight then during daylight. This will help to mitigate those inherent risks associated with night flying.