We’re talking about aerodynamics again this week. Today, an excerpt from the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge on the forces in climbs and descents.

Forces in Climbs

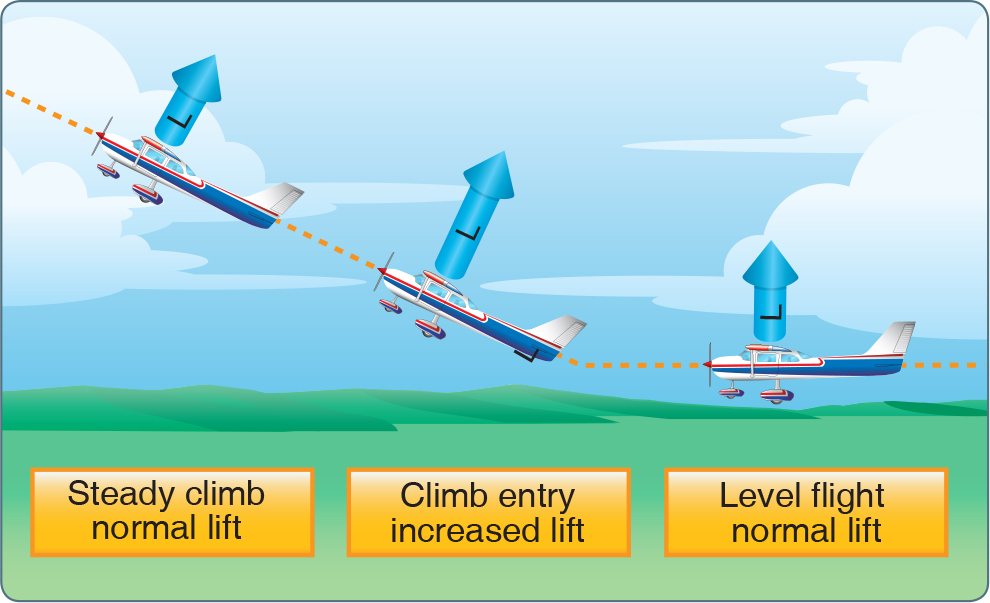

For all practical purposes, the wing’s lift in a steady state normal climb is the same as it is in a steady level flight at the same airspeed. Although the aircraft’s flight path changed when the climb was established, the angle of attack (AOA) of the wing with respect to the inclined flight path reverts to practically the same values, as does the lift. There is an initial momentary change as shown in the figure below. During the transition from straight-and-level flight to a climb, a change in lift occurs when back elevator pressure is first applied. Raising the aircraft’s nose increases the AOA and momentarily increases the lift. Lift at this moment is now greater than weight and starts the aircraft climbing. After the flight path is stabilized on the upward incline, the AOA and lift again revert to about the level flight values.

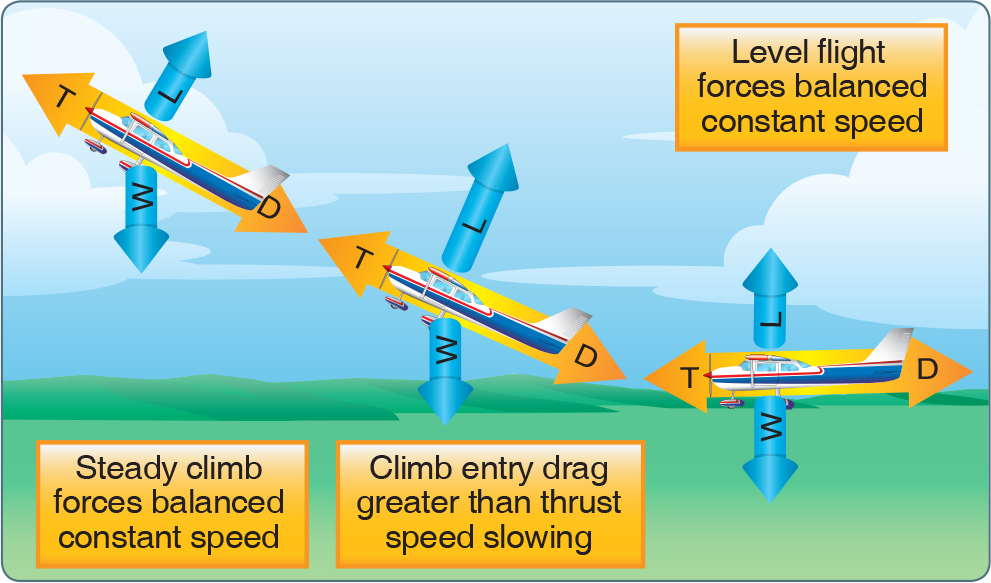

If the climb is entered with no change in power setting, the airspeed gradually diminishes because the thrust required to maintain a given airspeed in level flight is insufficient to maintain the same airspeed in a climb. When the flight path is inclined upward, a component of the aircraft’s weight acts in the same direction as, and parallel to, the total drag of the aircraft, thereby increasing the total effective drag. Consequently, the total effective drag is greater than the power, and the airspeed decreases. The reduction in airspeed gradually results in a corresponding decrease in drag until the total drag (including the component of weight acting in the same direction) equals the thrust. Due to momentum, the change in airspeed is gradual, varying considerably with differences in aircraft size, weight, total drag, and other factors. Consequently, the total effective drag is greater than the thrust, and the airspeed decreases.

Generally, the forces of thrust and drag, and lift and weight, again become balanced when the airspeed stabilizes but at a value lower than in straight-and-level flight at the same power setting. Since the aircraft’s weight is acting not only downward but rearward with drag while in a climb, additional power is required to maintain the same airspeed as in level flight. The amount of power depends on the angle of climb. When the climb is established steep enough that there is insufficient power available, a slower speed results.

The thrust required for a stabilized climb equals drag plus a percentage of weight dependent on the angle of climb. For example, a 10° climb would require thrust to equal drag plus 17 percent of weight. To climb straight up would require thrust to equal all of weight and drag. Therefore, the angle of climb for climb performance is dependent on the amount of excess thrust available to overcome a portion of weight. Note that aircraft are able to sustain a climb due to excess thrust. When the excess thrust is gone, the aircraft is no longer able to climb. At this point, the aircraft has reached its “absolute ceiling.”

Forces in Descents

As in climbs, the forces that act on the aircraft go through definite changes when a descent is entered from straight-and-level flight. For the following example, the aircraft is descending at the same power as used in straight-and-level flight.

As forward pressure is applied to the control yoke to initiate the descent, the AOA is decreased momentarily. Initially, the momentum of the aircraft causes the aircraft to briefly continue along the same flight path. For this instant, the AOA decreases causing the total lift to decrease. With weight now being greater than lift, the aircraft begins to descend. At the same time, the flight path goes from level to a descending flight path. Do not confuse a reduction in lift with the inability to generate sufficient lift to maintain level flight. The flight path is being manipulated with available thrust in reserve and with the elevator.

To descend at the same airspeed as used in straight-and-level flight, the power must be reduced as the descent is entered. Entering the descent, the component of weight acting forward along the flight path increases as the angle of descent increases and, conversely, when leveling off, the component of weight acting along the flight path decreases as the angle of descent decreases.