This week on the Learn to Fly Blog we’re talking about drag. One of the four forces of flight, drag opposes thrust and at rearward parallel to the relative wind. We’ll get more into the practical application of your understanding of drag on Thursday with our CFI, but today we will define the two types of aerodynamic drag: parasite drag and induced drag. Today’s post features excerpts from the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (8083-25).

Parasite Drag

Parasite drag is comprised of all the forces that work to slow an aircraft’s movement. As the term parasite implies, it is the drag that is not associated with the production of lift. This includes the displacement of the air by the aircraft, turbulence generated in the airstream, or a hindrance of air

moving over the surface of the aircraft and airfoil. There are three types of parasite drag: form drag, interference drag, and skin friction.

Form Drag

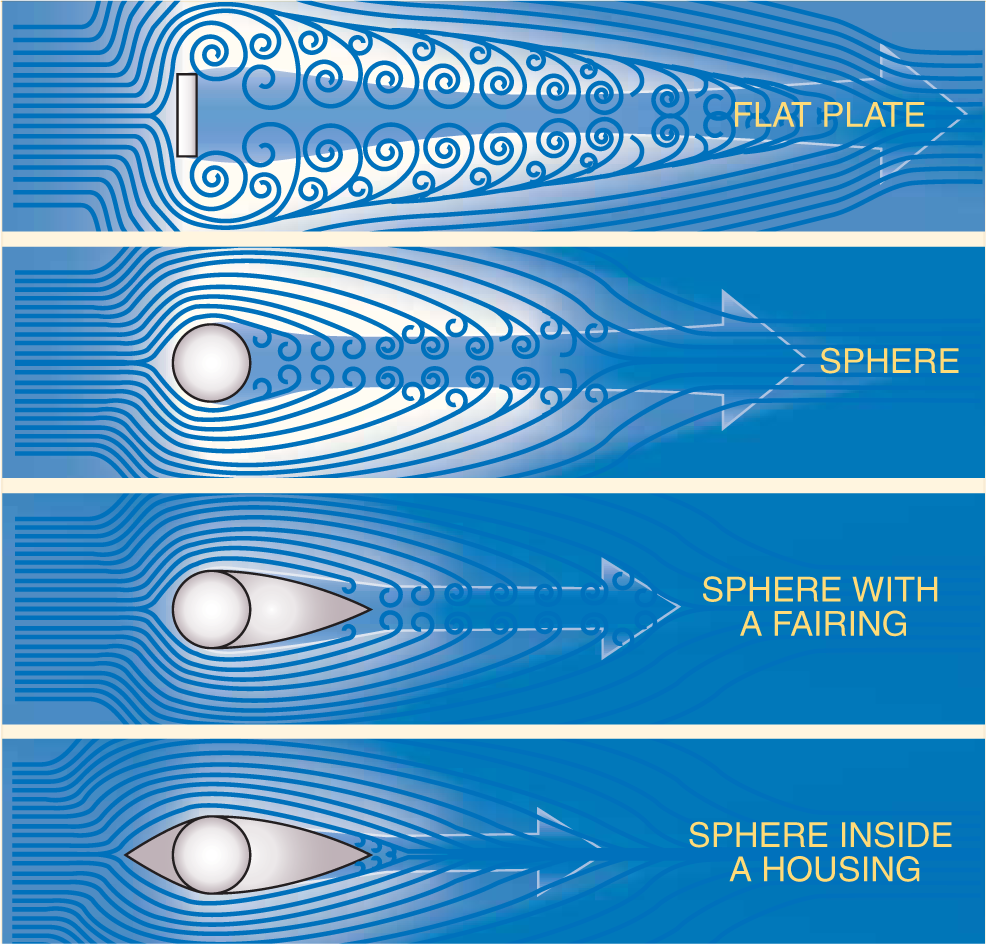

Form drag is the portion of parasite drag generated by the aircraft due to its shape and airflow around it. Examples include the engine cowlings, antennas, and the aerodynamic shape of other components. When the air has to separate to move around a moving aircraft and its components, it eventually rejoins after passing the body. How quickly and smoothly it rejoins is representative of the resistance that it creates which requires additional force to overcome.

Notice how the flat plate in Figure 4-5 causes the air to swirl around the edges until it eventually rejoins downstream. Form drag is the easiest to reduce when designing an aircraft. The solution is to streamline as many of the parts as possible.

Interference Drag

Interference drag comes from the intersection of airstreams that creates eddy currents, turbulence, or restricts smooth airflow. For example, the intersection of the wing and the fuselage at the wing root has significant interference drag. Air flowing around the fuselage collides with air flowing over the wing, merging into a current of air different from the two original currents. The most interference drag is observed when two surfaces meet at perpendicular angles. Fairings are used to reduce this tendency. If a jet fighter carries two identical wing tanks, the overall drag is greater than the sum of the individual tanks because both of these create and generate interference drag. Fairings and distance between lifting surfaces and external components (such as radar antennas hung from wings) reduce interference drag.

Skin Friction Drag

Skin friction drag is the aerodynamic resistance due to the contact of moving air with the surface of an aircraft. Every surface, no matter how apparently smooth, has a rough, ragged surface when viewed under a microscope. The air molecules, which come in direct contact with the surface of the wing, are virtually motionless. Each layer of molecules above the surface moves slightly faster until the molecules are moving at the velocity of the air moving around the aircraft. This speed is called the free-stream velocity. The area between the wing and the free-stream velocity level is about as wide as a playing card and is called the boundary layer. At the top of the boundary layer, the molecules increase velocity and move at the same speed as the molecules outside the boundary layer. The actual speed at which the molecules move depends upon the shape of the wing, the viscosity (stickiness) of the air through which the wing or airfoil is moving, and its compressibility (how much it can be compacted).

The airflow outside of the boundary layer reacts to the shape of the edge of the boundary layer just as it would to the physical surface of an object. The boundary layer gives any object an “effective” shape that is usually slightly different from the physical shape. The boundary layer may also separate from the body, thus creating an effective shape much different from the physical shape of the object. This change in the physical shape of the boundary layer causes a dramatic decrease in lift and an increase in drag. When this happens, the airfoil has stalled.

In order to reduce the effect of skin friction drag, aircraft designers utilize flush mount rivets and remove any irregularities which may protrude above the wing surface. In addition, a smooth and glossy finish aids in transition of air across the surface of the wing. Since dirt on an aircraft disrupts the free flow of air and increases drag, keep the surfaces of an aircraft clean and waxed.

Induced Drag

The second basic type of drag is induced drag. It is an established physical fact that no system that does work in the mechanical sense can be 100 percent efficient. This means that whatever the nature of the system, the required work is obtained at the expense of certain additional work that is dissipated or lost in the system. The more efficient the system, the smaller this loss.

In level flight the aerodynamic properties of a wing or rotor produce a required lift, but this can be obtained only at the expense of a certain penalty. The name given to this penalty is induced drag. Induced drag is inherent whenever an airfoil is producing lift and, in fact, this type of drag is inseparable from the production of lift. Consequently, it is always present if lift is produced.

An airfoil (wing or rotor blade) produces the lift force by making use of the energy of the free airstream. Whenever an airfoil is producing lift, the pressure on the lower surface of it is greater than that on the upper surface (Bernoulli’s Principle). As a result, the air tends to fl ow from the high pressure area below the tip upward to the low pressure area on the upper surface. In the vicinity of the tips, there is a tendency for these pressures to equalize, resulting in a lateral flow outward from the underside to the upper surface. This lateral flow imparts a rotational velocity to the air at the tips, creating vortices, which trail behind the airfoil.

When the aircraft is viewed from the tail, these vortices circulate counterclockwise about the right tip and clockwise about the left tip. Bearing in mind the direction of rotation of these vortices, it can be seen that they induce an upward flow of air beyond the tip, and a downwash flow behind the wing’s trailing edge. This induced downwash has nothing in common with the downwash that is necessary to produce lift. It is, in fact, the source of induced drag. The greater the size and strength of the vortices and consequent downwash component on the net airflow over the airfoil, the greater the induced drag effect becomes. This downwash over the top of the airfoil at the tip has the same effect as bending the lift vector rearward; therefore, the lift is slightly aft of perpendicular to the relative wind, creating a rearward lift component. This is induced drag.

In order to create a greater negative pressure on the top of an airfoil, the airfoil can be inclined to a higher AOA. If the AOA of a symmetrical airfoil were zero, there would be no pressure differential, and consequently, no downwash component and no induced drag. In any case, as AOA increases, induced drag increases proportionally. To state this another way—the lower the airspeed the greater the AOA required to produce lift equal to the aircraft’s weight and, therefore, the greater induced drag. The amount of induced drag varies inversely with the square of the airspeed.

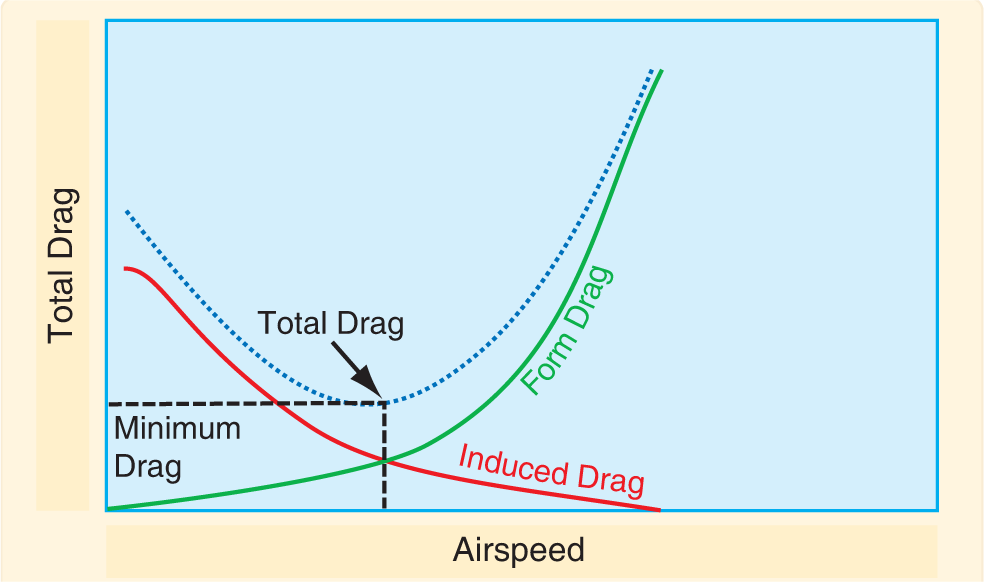

Conversely, parasite drag increases as the square of the airspeed. Thus, as airspeed decreases to near the stalling speed, the total drag becomes greater, due mainly to the sharp rise in induced drag. Similarly, as the airspeed reaches the terminal velocity of the aircraft, the total drag again increases rapidly, due to the sharp increase of parasite drag. As seen in the chart below, at some given airspeed, total drag is at its minimum amount. In figuring the maximum endurance and range of aircraft, the power required to overcome drag is at a minimum if drag is at a minimum.