Effective communication is absolutely critical to your safety and the safety of those in the air around you and on the ground. There’s a well established phraseology and accepted techniques in aviation, so mastering this will be key in your flight training. Take a look at the introduction to radio communications, excerpted from Bob Gardner’s communication textbook Say Again, Please, as well as our CFI’s post on how the FAA expects you to understand radio phraseology. Today’s post comes from Bob Gardner’s The Complete Private Pilot and from the FAR/AIM.

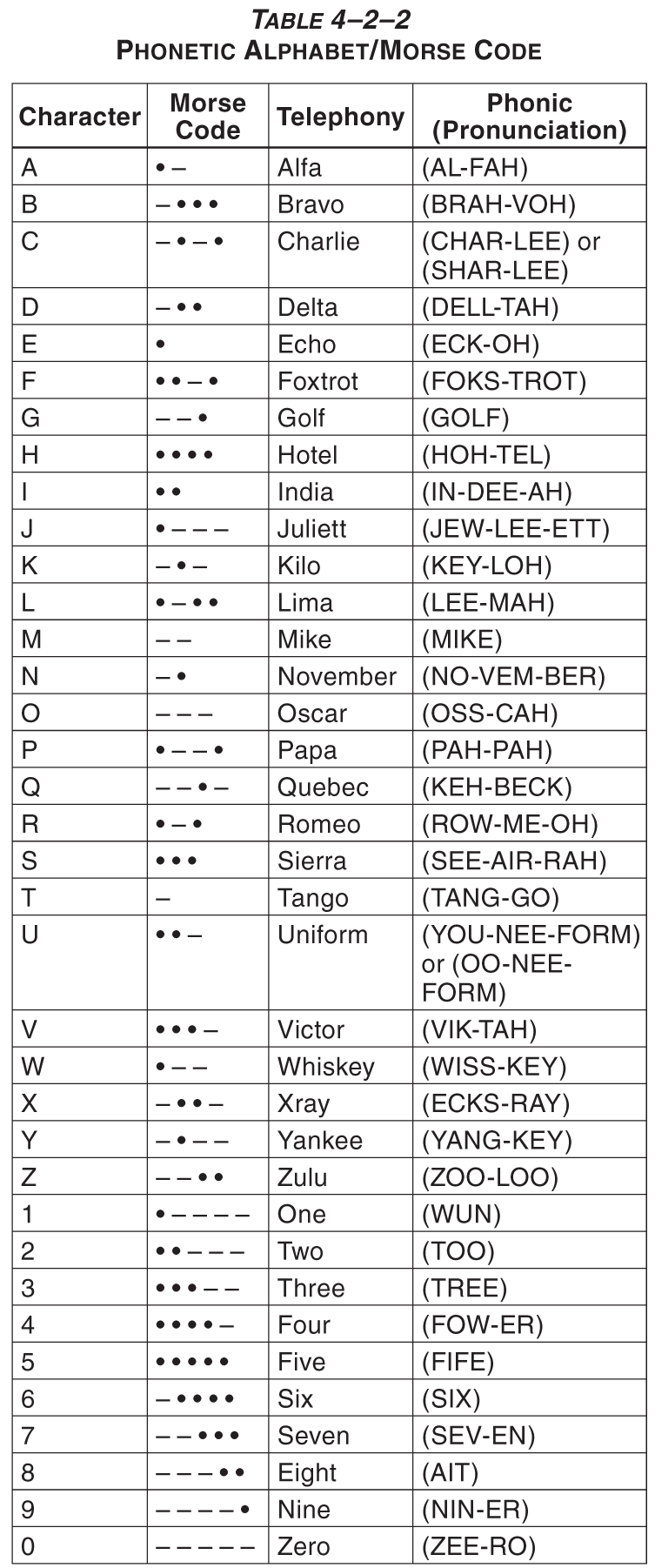

Always use the phonetic alphabet when identifying your aircraft and to spell out groups of letter or unusual words under difficult communications conditions. Do not make up your own phonetic equivalents; this alphabet was developed internationally to be understandable by non-English speaking pilots and ground personnel.

Misunderstandings about altitude assignments can be hazardous. Check the Aeronautical Information Manual for more officially accepted techniques. However, as you monitor aviation frequencies you will hear pilots use a decimal system: TWO POINT FIVE for 2,500. The FAA has never commented on this practice and it is commonly accepted—don’t try it in another country.

500 . . . . . . . FIVE HUNDRED

10,000 . . . . . TEN THOUSAND

13,500 . . . . . ONE THREE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED

Pilots flying above 18,000 feet use flight levels when referring to altitude:

“CENTURION 45X LEAVING ONE SEVEN THOUSAND FOR FLIGHT LEVEL TWO THREE ZERO.”

Bearings, courses, and radials are always spoken in three digits:

“CESSNA 38N TURN LEFT HEADING THREE ZERO ZERO, INTERCEPT THE DALLAS ZERO ONE FIVE RADIAL.”

Address ground controllers as “SEATTLE GROUND CONTROL,” control towers as “O’HARE TOWER,” radar facilities as “MIAMI APPROACH,” or “ATLANTA CENTER.” When calling a flight service station, use radio: “PORTLAND RADIO, MOONEY FOUR VICTOR WHISKEY.”

When making the initial contact with a controller, use your full callsign, without the initial november: “BOISE GROUND, PIPER THREE SIX NINER ECHO ROMEO AT THE RAMP WITH INFORMATION GOLF, TAXI FOR TAKEOFF.”

Many uncontrolled airports share UNICOM frequencies, and if you do not identify the airport at which you are operating, your transmissions may serve to confuse other pilots monitoring the frequency. Don’t say, “STINSON FOUR SIX WHISKEY DOWNWIND FOR RUNWAY SIX,” say, “ARLINGTON TRAFFIC, STINSON FOUR SIX WHISKEY DOWNWIND FOR RUNWAY SIX, ARLINGTON.” That way, pilots at other airports sharing Arlington’s UNICOM frequency will not be nervously looking over their shoulders.

The most valuable word in radio communication is “unable.” It should be used whenever you are asked to do something you don’t want to do or are prohibited from doing, like flying to close to a cloud. An air traffic controller who hears “unable” will come up with an alternative plan. You are the pilot-in-command and the only person in position to determine the safety of a proposed action. The second most important word is “immediately.” If a controller tells you to turn left immediately, or to climb immediately or to do anything else immediately, do not reach for the microphone—do it. The other side of the coin is when you need to cut corners to get on the ground in a hurry—a sick passenger, for example. When you make your initial call, tell the controller that you need to land immediately.

Online Resources

www.flyagogo.net

www.ourairports.com

www.skyvector.com

www.aopa.org/airports

Note: None of these sites are official and they should be used only for planning and orientation. Aerial views are not current.

You can find the frequencies to be used at any airport at www.airnav.com.

An excellent resource for radio communication procedures is “Say it Right,” produced by the Air Safety Foundation. It can be found at www.asf.org/courses.

More on communication procedures from our CFI on Thursday.