Today’s post is excerpted from the brand-new edition of the Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3) available now in print and ebook from ASA.

The round out is a slow, smooth transition from a normal approach attitude to a landing attitude, gradually rounding out the flightpath to one that is parallel with, and within a very few inches above, the runway. When the airplane, in a normal descent, approaches within what appears to be 10 to 20 feet above the ground, the round out or flare is started. This is a continuous process until the airplane touches down on the ground.

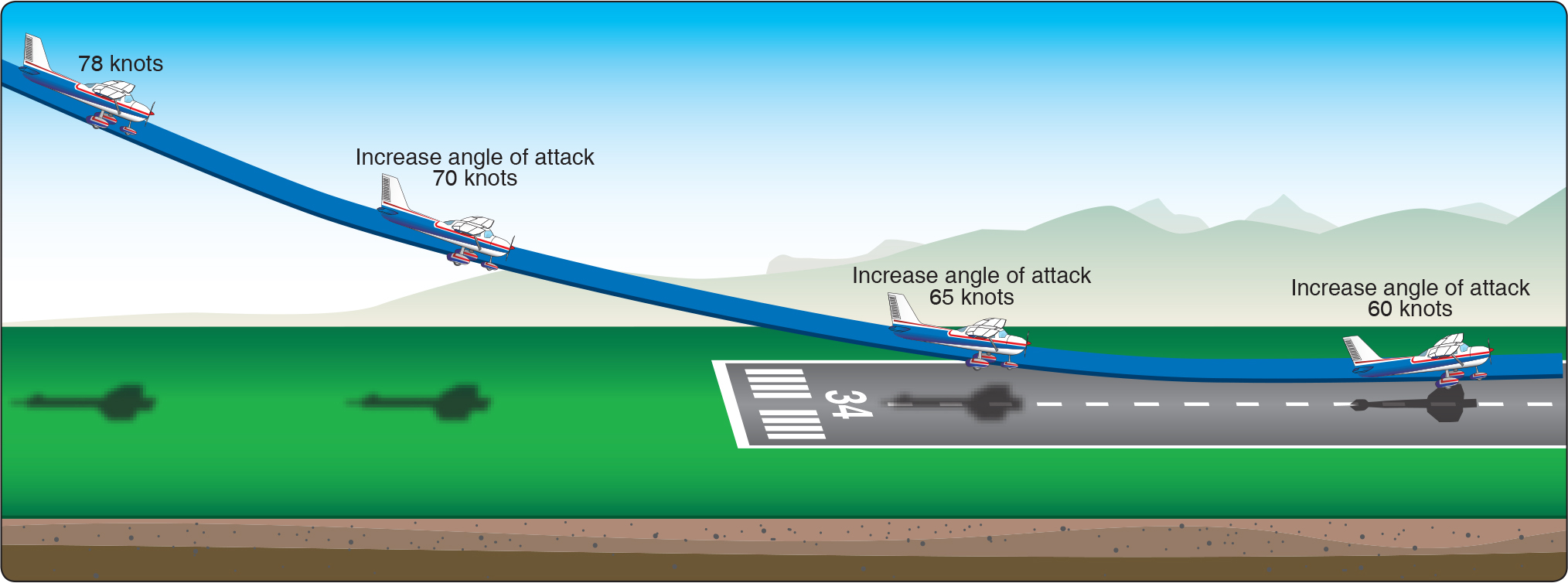

As the airplane reaches a height above the ground where a change into the proper landing attitude can be made, back-elevator pressure is gradually applied to slowly increase the pitch attitude and angle of attack (AOA). This causes the airplane’s nose to gradually rise toward the desired landing attitude. The AOA is increased at a rate that allows the airplane to continue settling slowly as forward speed decreases.

When the AOA is increased, the lift is momentarily increased and this decreases the rate of descent. Since power normally is reduced to idle during the round out, the airspeed also gradually decreases. This causes lift to decrease again and necessitates raising the nose and further increasing the AOA. During the round out, the airspeed is decreased to touchdown speed while the lift is controlled so the airplane settles gently onto the landing surface. The round out is executed at a rate that the proper landing attitude and the proper touchdown airspeed are attained simultaneously just as the wheels contact the landing surface.

The rate at which the round out is executed depends on the airplane’s height above the ground, the rate of descent, and the pitch attitude. A round out started excessively high must be executed more slowly than one from a lower height to allow the airplane to descend to the ground while the proper landing attitude is being established. The rate of rounding out must also be proportionate to the rate of closure with the ground. When the airplane appears to be descending very slowly, the increase in pitch attitude must be made at a correspondingly slow rate.

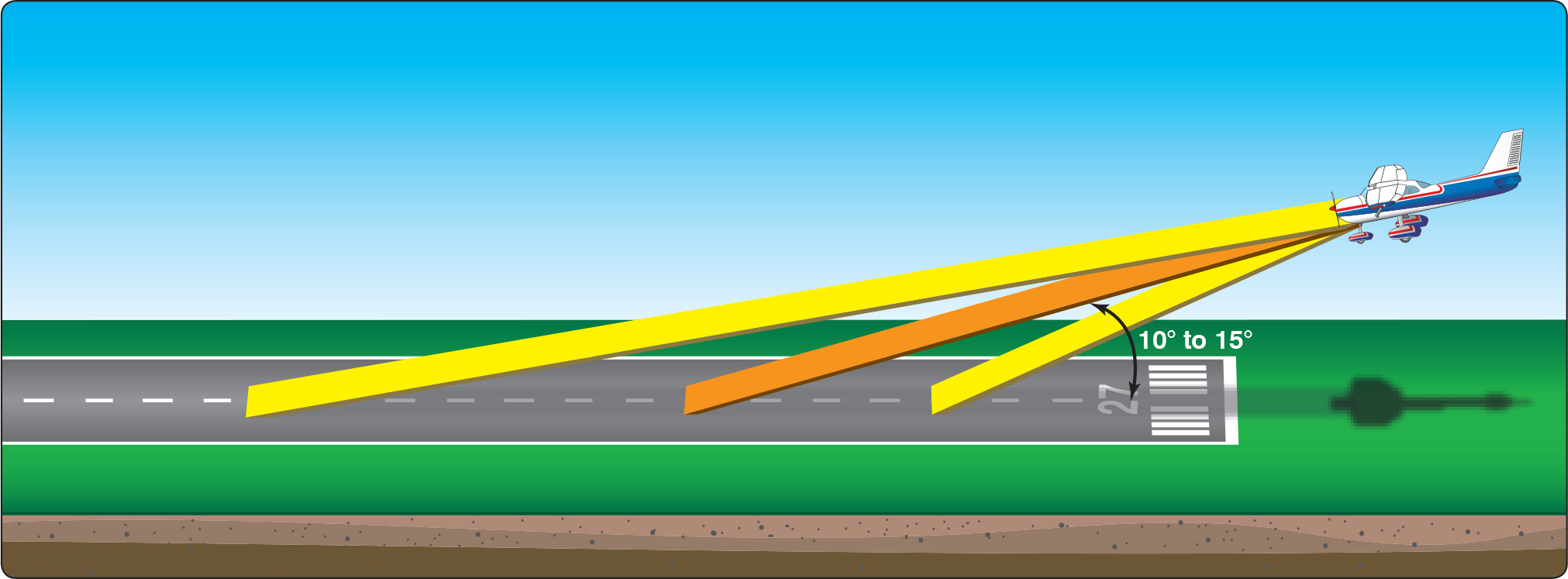

Visual cues are important in flaring at the proper altitude and maintaining the wheels a few inches above the runway until eventual touchdown. Flare cues are primarily dependent on the angle at which the pilot’s central vision intersects the ground (or runway) ahead and slightly to the side. Proper depth perception is a factor in a successful flare, but the visual cues used most are those related to changes in runway or terrain perspective and to changes in the size of familiar objects near the landing area, such as fences, bushes, trees, hangars, and even sod or runway texture. Focus direct central vision at a shallow downward angle from 10° to 15° toward the runway as the round out/flare is initiated. Maintaining the same viewing angle causes the point of visual interception with the runway to move progressively rearward as the airplane loses altitude. This is an important visual cue in assessing the rate of altitude loss. Conversely, forward movement of the visual interception point indicates an increase in altitude and means that the pitch angle was increased too rapidly, resulting in an over flare. Location of the visual interception point in conjunction with assessment of flow velocity of nearby off-runway terrain, as well as the similarity of appearance of height above the runway ahead of the airplane (in comparison to the way it looked when the airplane was taxied prior to takeoff), is also used to judge when the wheels are just a few inches above the runway.

The pitch attitude of the airplane in a full-flap approach is considerably lower than in a no-flap approach. To attain the proper landing attitude before touching down, the nose must travel through a greater pitch change when flaps are fully extended. Since the round out is usually started at approximately the same height above the ground regardless of the degree of flaps used, the pitch attitude must be increased at a faster rate when full flaps are used; however, the round out is still be executed at a rate proportionate to the airplane’s downward motion.

Once the actual process of rounding out is started, do not push the elevator control forward. If too much back-elevator pressure was exerted, this pressure is either slightly relaxed or held constant, depending on the degree of the error. In some cases, it may be necessary to advance the throttle slightly to prevent an excessive rate of sink or a stall, either of which results in a hard, drop-in type landing.

It is recommended that a pilot form the habit of keeping one hand on the throttle throughout the approach and landing should a sudden and unexpected hazardous situation require an immediate application of power.