We tend to think of piloting an airplane as a physical skill, but there is much more to it. The pilot must assemble information, interpret data, assess its importance, make decisions, act, communicate, correct and continually reasses. Over time, all of this contributes to fatigue. Today on the Learn to Fly Blog we’ll talk about mental workload. This post is excerpted from The Pilot’s Manual Volume 2: Ground School.

Best performance is achieved by a combination of high levels of skill, knowledge, and experience (consistency and confidence), and with an optimum degree of arousal. Skill, knowledge and experience depend upon the training of the pilot; the degree of arousal depends not only upon the pilot’s flying ability but also upon other factors, such as the design of the cockpit, air traffic control, as well as upon the environment, motivation, personal life, weather, and so on. Low levels of skill, knowledge and experience, plus a poorly designed cockpit, bad weather, and poor controlling will lead to a high mental workload and a poor performance. If the mental workload becomes too high, decision making will deteriorate in quality, or maybe not even occur. This could result in concentrating only on one task (sometimes called tunnel vision) with excessive or inappropriate load-shedding. You can raise your capability by studying and practicing, and by being fit, relaxed and well rested.

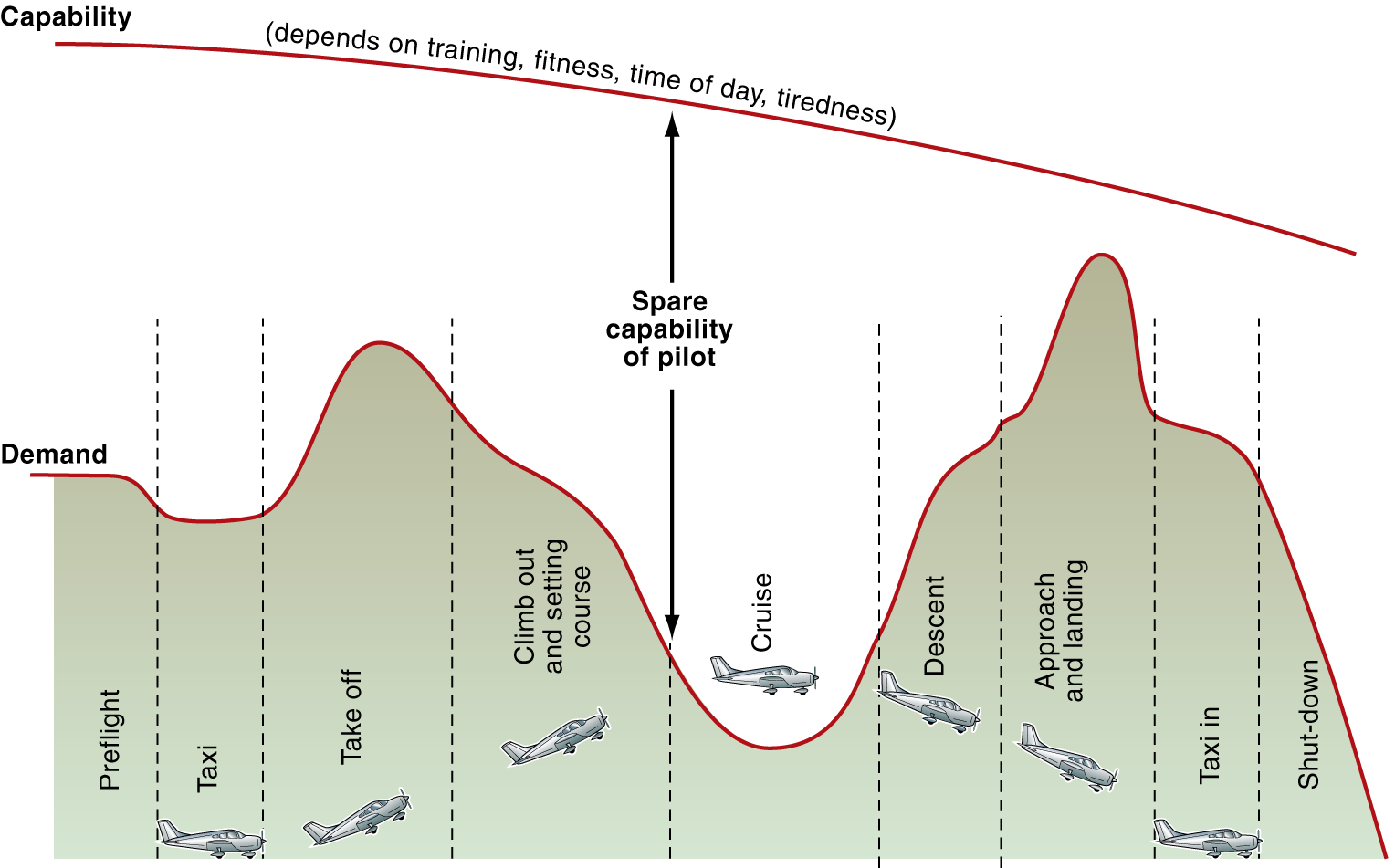

The pilot’s tasks need to be analyzed so that at no time do they demand more of the pilot than the average, current and fit pilot is capable of delivering. There should always be some reserve capacity to allow for handling unexpected abnormal and emergency situations. At the aircraft design stage, the pilot is taken to be of an average standard. On this basis, skills and responses are established during testing so that the aircraft can be certificated as compliant. But there is some argument that the specimen should not be the average pilot, because half of the pilot population would be below this standard.

The legislators establish the minimum acceptable standards for licensing but the marginal pilot, who maintains only the minimum required standard, is not really of an acceptable standard. You can each ensure that you are at an acceptable standard by honestly reviewing the demand that the aircraft and the flight placed upon you. If your capabilities, mental or physical, were stretched at all, then you need more practice, more study or more training—at least in those aspects that challenged you. Many pilots feel that, under normal conditions, they should be able to operate at only 40–50% of capacity, except during takeoffs and landings, when that might rise to 70%. This leaves some capacity to handle abnormal situations.