Short-field approaches and landings require the use of procedures for approaches and landings at fields with a relatively short landing area or where an approach is made over obstacles that limit the available landing area. Short-field operations require the pilot fly the airplane at one of its crucial performance capabilities while close to the ground in order to safely land within confined areas. This low-speed type of power-on approach is closely related to the performance of flight at minimum controllable airspeeds. Today’s post is an excerpt from the Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-8083-3).

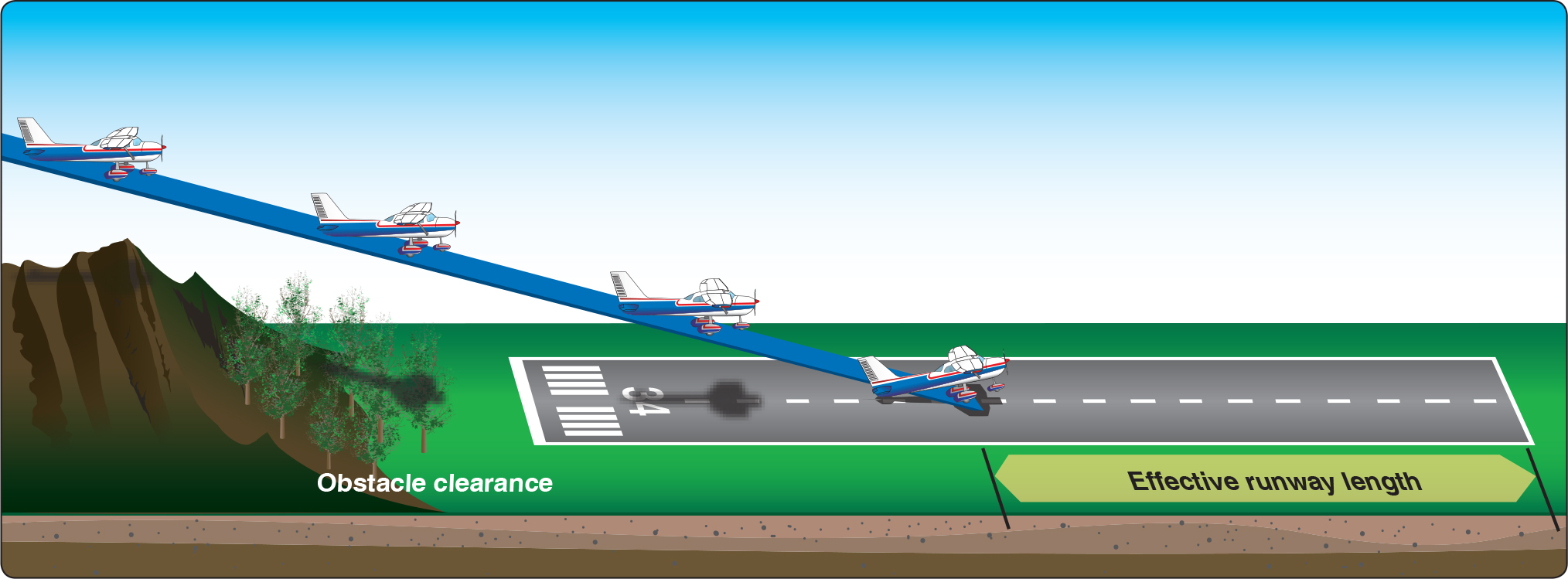

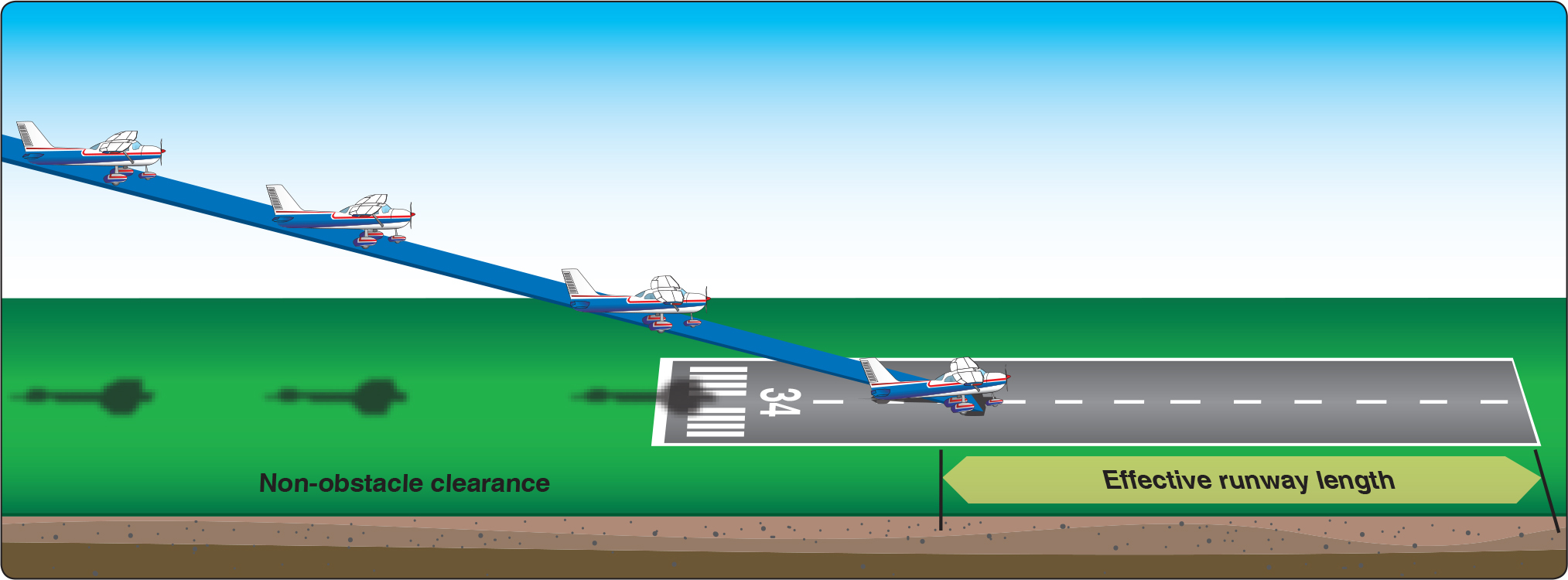

To land within a short-field or a confined area, the pilot must have precise, positive control of the rate of descent and airspeed to produce an approach that clears any obstacles, result in little or no floating during the round out, and permit the airplane to be stopped in the shortest possible distance.

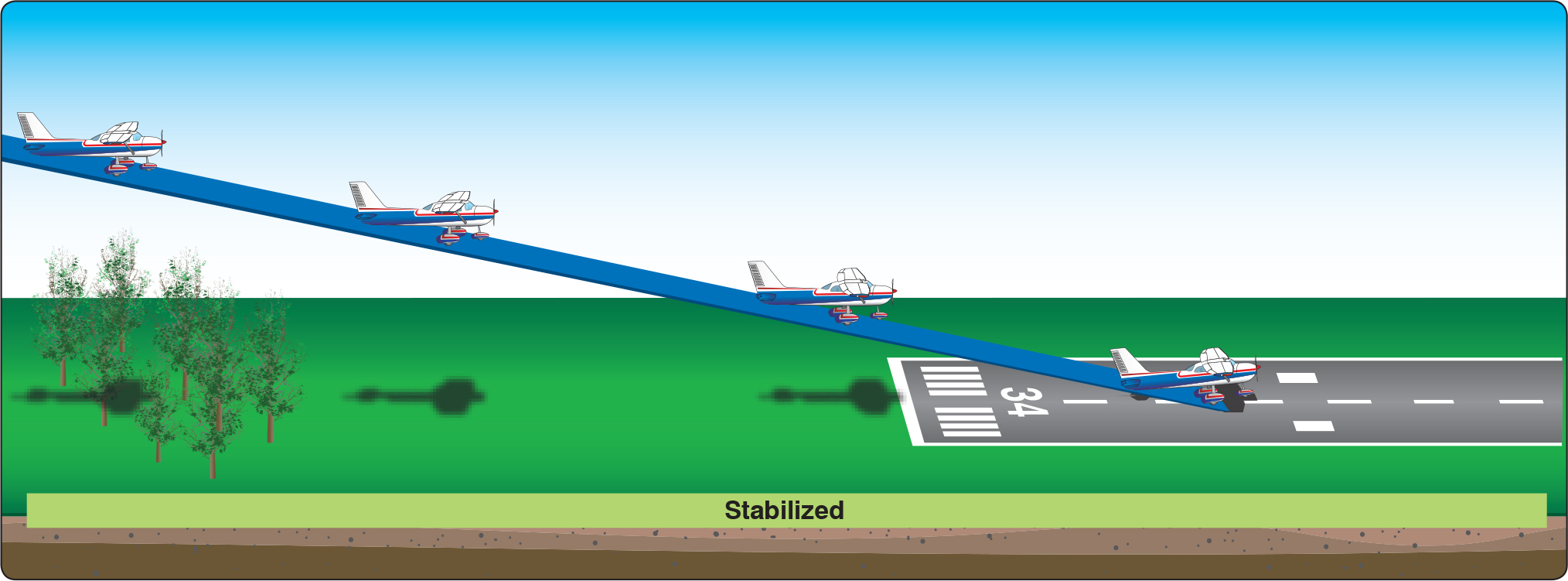

The procedures for landing in a short-field or for landing approaches over obstacles as recommended in the AFM/ POH should be used. A stabilized approach is essential. These procedures generally involve the use of full flaps and the final approach started from an altitude of at least 500 feet higher than the touchdown area. A wider than normal pattern is normally used so that the airplane can be properly configured and trimmed. In the absence of the manufacturer’s recommended approach speed, a speed of not more than 1.3 VSO is used. For example, in an airplane that stalls at 60 knots with power off, and flaps and landing gear extended, an approach speed no higher than 78 knots is used. In gusty air, no more than one-half the gust factor is added. An excessive amount of airspeed could result in a touchdown too far from the runway threshold or an after landing roll that exceeds the available landing area. After the landing gear and full flaps have been extended, simultaneously adjust the power and the pitch attitude to establish and maintain the proper descent angle and airspeed. A coordinated combination of both pitch and power adjustments is required. When this is done properly, very little change in the airplane’s pitch attitude and power setting is necessary to make corrections in the angle of descent and airspeed.

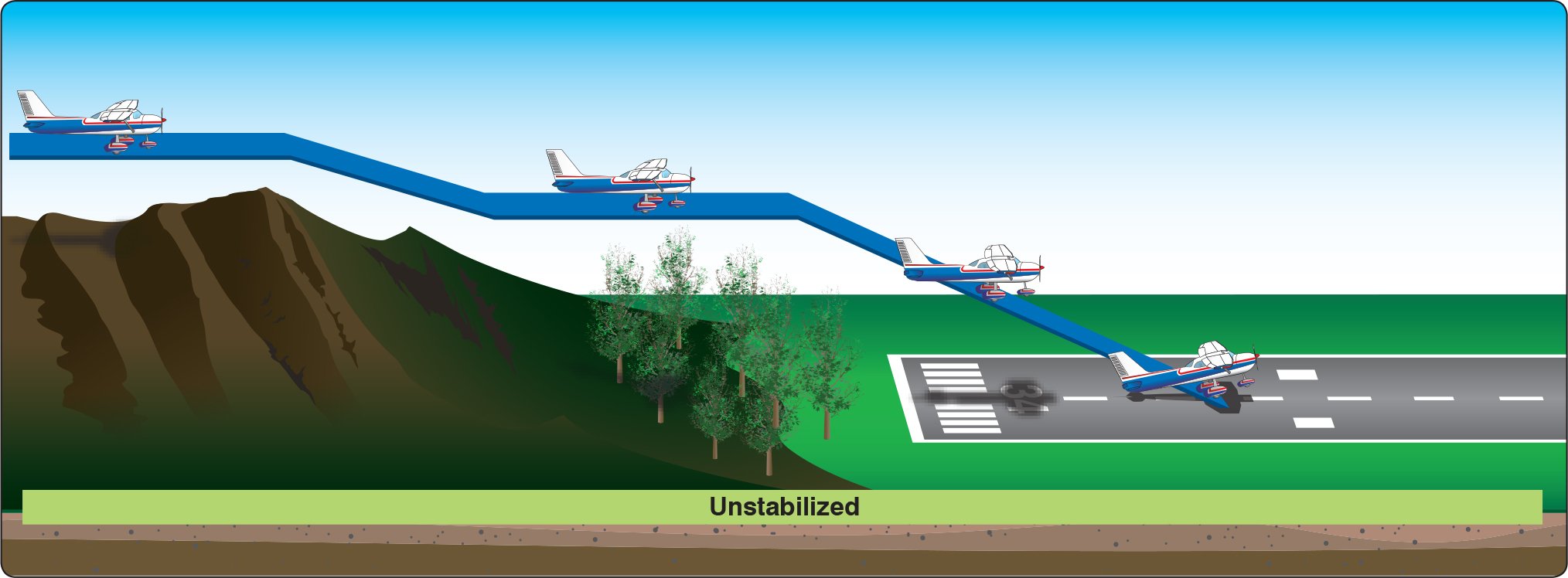

The short-field approach and landing is in reality an accuracy approach to a spot landing. The procedures previously outlined in the section on the stabilized approach concept are used. If it appears that the obstacle clearance is excessive and touchdown occurs well beyond the desired spot leaving insufficient room to stop, power is reduced while lowering the pitch attitude to steepen the descent path and increase the rate of descent. If it appears that the descent angle does not ensure safe clearance of obstacles, power is increased while simultaneously raising the pitch attitude to shallow the descent path and decrease the rate of descent. Care must be taken to avoid an excessively low airspeed. If the speed is allowed to become too slow, an increase in pitch and application of full power may only result in a further rate of descent. This occurs when the AOA is so great and creating so much drag that the maximum available power is insufficient to overcome it. This is generally referred to as operating in the region of reversed command or operating on the back side of the power curve. When there is doubt regarding the outcome of the approach, make a go around and try again or divert to a more suitable landing area.

Because the final approach over obstacles is made at a relatively steep approach angle and close to the airplane’s stalling speed, the initiation of the round out or flare must be judged accurately to avoid flying into the ground or stalling prematurely and sinking rapidly. A lack of floating during the flare with sufficient control to touch down properly is verification that the approach speed was correct.

Touchdown should occur at the minimum controllable airspeed with the airplane in approximately the pitch attitude that results in a power-off stall when the throttle is closed. Care must be exercised to avoid closing the throttle too rapidly, as closing the throttle may result in an immediate increase in the rate of descent and a hard landing.

Upon touchdown, the airplane is held in this positive pitch attitude as long as the elevators remain effective. This provides aerodynamic braking to assist in deceleration. Immediately upon touchdown and closing the throttle, appropriate braking is applied to minimize the after-landing roll. The airplane is normally stopped within the shortest possible distance consistent with safety and controllability. If the proper approach speed has been maintained, resulting in minimum float during the round out and the touchdown made at minimum control speed, minimum braking is required.

Common errors in the performance of short-field approaches and landings are:

- Failure to allow enough room on final to set up the approach, necessitating an overly steep approach and high sink rate

- Unstable approach

- Undue delay in initiating glide path corrections

- Too low an airspeed on final resulting in inability to flare properly and landing hard

- Too high an airspeed resulting in floating on round out

- Prematurely reducing power to idle on round out resulting in hard landing

- Touchdown with excessive airspeed

- Excessive and/or unnecessary braking after touchdown

- Failure to maintain directional control

- Failure to recognize and abort a poor approach that cannot be completed safely